Perspectives on the Ethics of Public Shaming

Contents

18.3. Perspectives on the Ethics of Public Shaming#

We previously looked at how shame might play out in childhood development, let’s look at different views of people being shamed in public.

18.3.1. Weak against strong#

Jennifer Jacquet argues that shame can be morally good as a tool the weak can use against the strong:

The real power of shame is it can scale. It can work against entire countries and can be used by the weak against the strong. Guilt, on the other hand, because it operates entirely within individual psychology, doesn’t scale.

[…]

We still care about individual rights and protection. Transgressions that have a clear impact on broader society – like environmental pollution – and transgressions for which there is no obvious formal route to punishment are, for instance, more amenable to its use. It should be reserved for bad behaviour that affects most or all of us.

[…]

A good rule of thumb is to go after groups, but I don’t exempt individuals, especially not if they are politically powerful or sizeably impact society. But we must ask ourselves about the way those individuals are shamed and whether the punishment is proportional.

18.3.2. Schadenfreude#

Another way of considering public shaming is as schadenfreude, meaning the enjoyment obtained from the troubles of others.

A 2009 satirical article from the parody news site The Onion satirizes public shaming as being for objectifying celebrities and being entertained by their misfortune:

Media experts have been warning for months that American consumers will face starvation if Hollywood does not provide someone for them to put on a pedestal, worship, envy, download sex tapes of, and then topple and completely destroy.

18.3.3. Normal People#

While the example from The Onion above focuses on celebrity, in the time since it was written, social media has taken a larger role in society and democratized celebrity. As comedian Bo Burnham puts it:

“[This] celebrity pressure I had experienced on stage has now been democratized and given to everybody [through social media]. And everyone is feeling this pressure of having an audience, of having to perform, of having a sort of, like, proper noun version of your own name and then the self in your heart.” (NPR Fresh Air Interview)

Also, Rebecca Jennings worries about how public shaming is used against “normal” people who are plucked out of obscurity to be shamed by huge crowds online:

“Millions of people became invested in this (niche! not very interesting!) drama because it gives us something easy to be angry or curious or self-righteous about, something to project our own experiences onto, and thereby contributing even more content to the growing avalanche. Naturally, some decided to go look up the central character’s address, phone number, and workplace and share it on the internet.

[…]

‘It’s on social media, so it’s public!’ one could argue as a case for people’s right to act like forensic analysts on social media, and that is true. But this justification is typically valid when a) the person posting is someone of note, like a celebrity or a politician, and b) when the stakes are even a little bit high. In most cases of normal-person canceling, neither standard is met. Instead, it’s mob justice and vigilante detective work typically reserved for, say, unmasking the Zodiac killer, except weaponized against normal people.

[…]

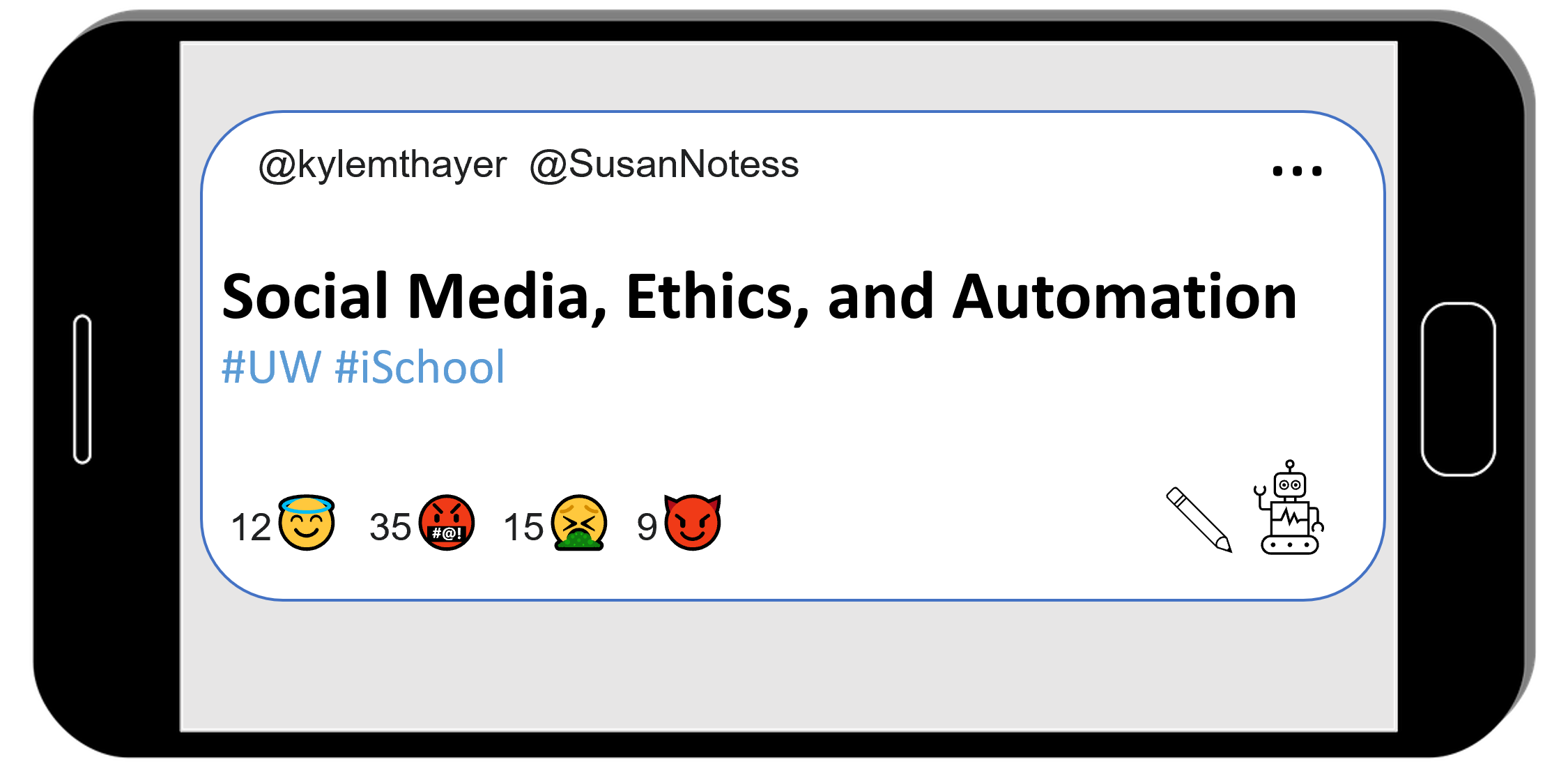

Platforms like TikTok, where even people with few or no followers often go viral overnight, expedite the shaming process.

18.3.4. Enforcing Norms#

In the philosophy paper Enforcing Social Norms: The Morality of Public Shaming, Paul Billingham and Tom Parr discuss under what conditions public shaming would be morally permissible. They are concerned not with actions primarily intended to induce shame in the target, but rather actions that may cause a person to shame, but are motivated by “seeking to draw attention to a social norm violation, and to rally others to their cause.”

In this situation, they outline the following constraints that must be considered when publicly shaming someone in this way:

Proportionality: The negative consequences of shaming someone should not be worse than the positive consequences

Necessity: There must not be another more effective method of achieving the goal

Respect for Privacy: There must not be unnecessary violations of privacy

Non-Abusiveness: The shaming must not use abusive tactics.

Reintegration “Public shaming must aim at, and make possible, the reintegration of the norm violator back into the community, rather than permanently stigmatizing them.”

18.3.5. Reflection questions#

What do you consider to be the most important factors in making an instance of public shaming bad?

What do you consider to be the most important factors in making an instance of public shaming good (if you think that is possible)?