Moderation and Ethics

Contents

14.5. Moderation and Ethics#

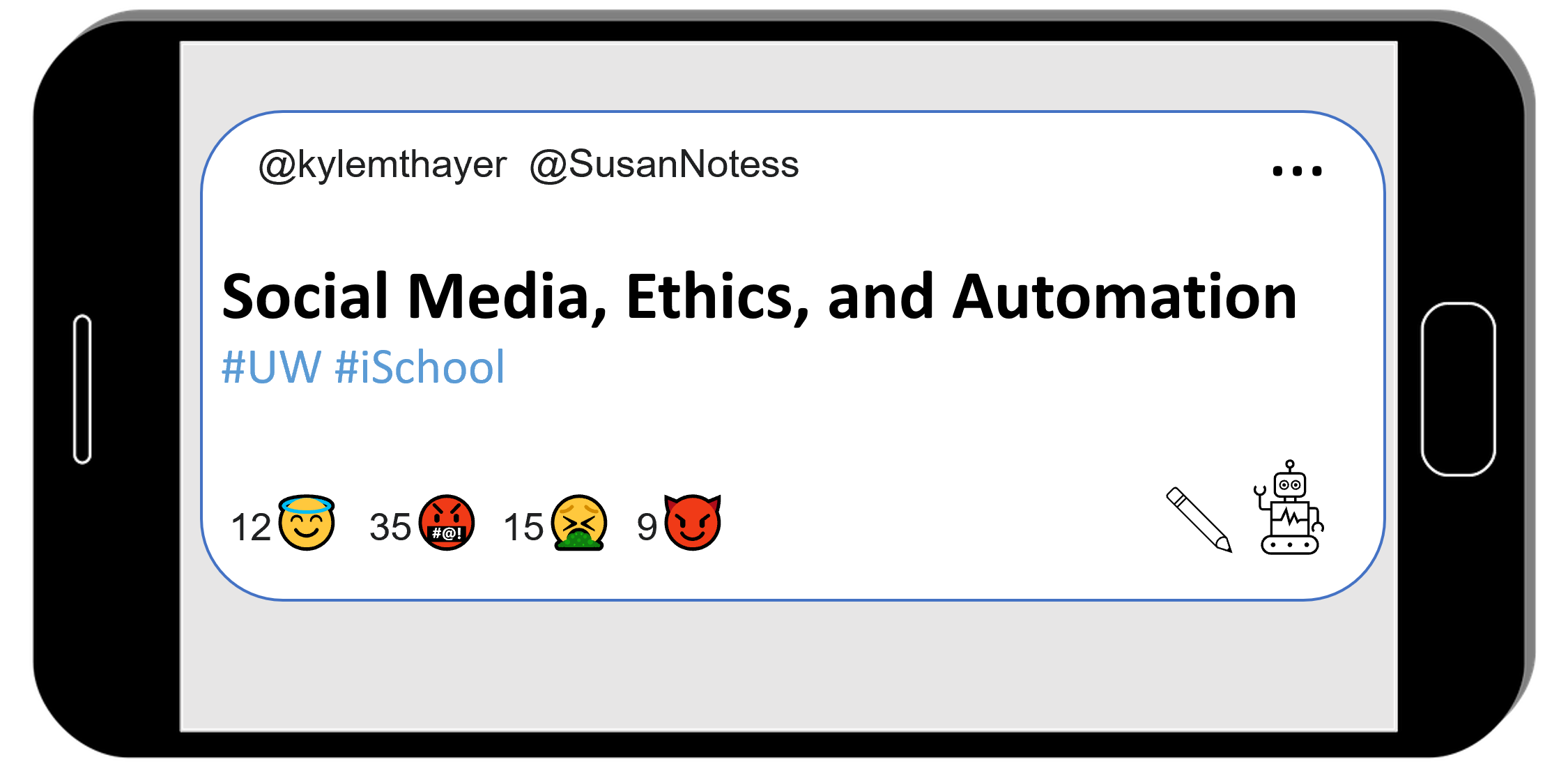

In the contexts of social media and public debate, moderation has a meaning that is about creating limits and boundaries about what is posted to keep things working well. But this meaning of “moderation” grew out of a wider, more generic concept of moderation. You might remember seeing moderation coming up in lists of virtues in virtue ethics, back in Chapter 2. So what does moderation (the social practice of limiting what is posted) have to do with moderation (the abstract ethical quality)?

14.5.1. Origin Story for Moderation#

One concept that comes up in a lot of different ethical frameworks is moderation. Famously, Confucian thinkers prized moderation as a sound principle for living, or as a virtue, and taught the value of the ‘golden mean’, or finding a balanced, moderate state between extremes. This golden mean idea got picked up by Aristotle—we might even say ripped off by Aristotle—as he framed each virtue as a medial state between two extremes. You could be cowardly at one extreme, or brash and reckless at the other; in the golden middle is courage. You could be miserly and penny-pinching, or you could be a reckless spender, but the aim is to find a healthy balance between those two. Moderation, or being moderate, is something that is valued in many ethical frameworks, not because it comes naturally to us, per se, but because it is an important part of how we form groups and come to trust each other for our shared survival and flourishing.

Moderation also comes up in deontological theories, including the political philosophy tradition that grew out of Kantian rationalism: the tradition that is often identified with John Rawls, although there are many other variations out there too. In brief, here is the journey of the idea:

Kant was influenced by ideas that were trending in his time–the European era we call the “Enlightenment”, which became very interested in the idea of rationality. We could write books about what they meant by the idea of “rationality”, and Kant certainly did so, but you probably already have a decent idea of what rationality is about. Rationalism tries to use reasoning, logical argument, and scientific evidence to figure out what to make of the world. Kant took this idea and ran with it, exploring the question of what if everything, even morality, could be derived from looking at rationality in the abstract.

Many philosophers and, let’s face it, many sensible people since Kant have questioned whether his project could succeed, or whether his question was even a good question to be asking. Can one person really get that kind of “god’s-eye view” of ultimate rationality? People disagree a lot about what would be the most rational way to live.

Some philosophers even suggested that it is hard to think about what is rational or reasonable without our take being skewed by our own aims and egos. We instinctively take whatever suits our own goals and frame it in the shape of reasons. Those who do not want their wealth taxed have reasons in the shape of rational arguments for why they should not be taxed. Those who do believe wealth should be taxed have reasons in the shape of rational arguments for why taxes should be imposed. Our motivations can massively affect which of those rationales we find to be most rational. This is what John Rawls wanted to address.

14.5.2. Rawls and Contractualism#

Rawls proposed a famous thought experiment. Imagine we were going to redesign America. A huge lottery was done to gather people from all walks of life into a committee to decide how the society should be structured and how it should function. Naturally, they will all have their own interests in mind, so Rawls proposed that they all be hidden behind a “veil of ignorance”, making it so that while they are on the committee, the people have no idea who they are, or what sort of life they will have once the new design is implemented. (The veil of ignorance is not a real thing, and it is extremely unclear how such an obscuring could be accomplished, although science fiction writers have had fun trying to imagine it.)

Rawls’s thought was that if you don’t know whether you will be in one of society’s more powerful roles or more disadvantaged roles, then you will have the motivation to make sure you will be okay, whatever role you get in the end. Therefore, the committee members would design a just and fair society, so that they would be okay no matter where they end up. The design the committee agrees to forms the basis of a new “social contract”, or agreement about how society works.

Theoretically, a social contract would guide us in how to live safely and fairly with each other, although injustice in the social contract means that these benefits are not always achieved. By “agreeing” to a social contract, we agree to let that contract moderate our natural rights as individual moral and rational agents. Natural Rights theory says no one should restrict my freedoms. Social Contract theory says that we use our freedom to accept certain restrictions, in order to make life better for all of us.

Rawlsian thought is usually classified as a form of Contractualism: although Rawls imagined the contractual agreement process as happening formally and explicitly, we can describe any society in a state of functioning equilibrium as operating on an implicit “social contract”. The social contract that guides a society can show up in informal guidelines (like customs, manners, and habits) and formal guidelines (like laws and regulations, such as we have for things like driving on roads, or for taxes). Those guidelines tell us how to function within the society.

Of course, a social contract involves more than just the formal, explicit parts. There are tacit and informal parts too, and that is where we find a lot of nuance. The United States’ Congress is not allowed to pass laws inhibiting your freedom of speech, but if you come over to my house and use your freedom in ways that I don’t care for, I can ask you to stop, or kick you out of my house. The existence of private property and private domains within that broader social contract means that we have the right to moderate spaces which belong to us. Like we saw with trolling, in Chapter 7, there are many ways that people can enforce patterns, habits, and norms, even without resorting to legal means.

![XKCD webcomic of a stick figure saying: "Public Service Announcement: The Right to Free Speech means the government can't arrest you for what you say. It doesn't mean that anyone else has to listen to your bullshit, or host you while you share it. The 1st Amendment doesn't shield you from criticism or consequences. If you're yelled at, boycotted, have your show canceled, or get banned from an Internet community, your free speech rights aren't being violated. It's just that the people listening think you're an asshole, [A picture of a partially open door is displayed.] And they're showing you the door."](../_images/free_speech_2x.png)

Fig. 14.2 An xkcd webcomic expressing an a view of free speech as related to the US Constitutions’ 1st amendment#

Because social media spaces involve a complicated interplay of privacy and publicity, they raise really complicated questions about what kinds of moderation are or should be legitimated by social contracts (either explicitly, by being spelled out in the Terms of Service, or implicitly, via downvoting, muting, or blocking), and what kinds of moderation are illegitimate obstructions to the rights of the individual to exercise free speech.

14.5.3. Charles W. Mills and The Racialized Contract#

Some philosophers, like Charles W. Mills, have pointed out that social contracts tend to be shaped by those in power, and agreed to by those in power, but they only work when a less powerful group is taken advantage of to support the power base of the contract deciders. This is a rough way of describing the idea behind Mills’s famous book, The Racial Contract. Mills said that the “we” of American society was actually a subgroup, a “we” within the broader community, and that the “we” of American society which agrees to the implicit social contract is a racialized “we”. That is, the contract is devised by and for, and agreed to by, white people, and it is rational–that is, it makes sense and it works–only because it assumes the subjugation and the exploitation of people of color. Mills argued that a truly just society would need to include ALL subgroups in devising and agreeing to the imagined social contract, instead of some subgroups using their rights and freedoms as a way to impose extra moderation on the rights and freedoms of other groups.

Reflection questions:

What people are in charge of different social media sites and the content moderation rules? How does this affect the rules that are made?

How might content moderation rules be different if all racial groups had power to set the rules?

14.5.4. Relational Ethics Frameworks#

You might be thinking here, what about all those other frameworks that didn’t focus so much on the individual, because they see the individual as inherently tied to and constituted by the social community? How do we determine what forms of moderation are legitimate or illegitimate if we begin from a place less obsessed with individual freedoms, and more attentive to the underlying elements of interconnectedness and care that we see forming the baseline for moral frameworks, like we see in the Ubuntu principle of some African Philosophies or in the care-based ecological ethics of many American Indigenous Philosophies?

Look at the Relational Ethics frameworks in chapter 2, and using those different frameworks:

What would be considered bad actions that need to be moderated?

What would be the goals of doing content moderation?

How might this look different than current content moderation systems?