17.4. Ethics and Harassment#

17.4.1. Moderation and Violence#

You might remember from Chapter 14 that social contracts, whether literal or metaphorical, involve groups of people all accepting limits to their freedoms. Because of this, some philosophers say that a state or nation is, fundamentally, violent. Violence in this case refers to the way that individual Natural Rights and freedoms are violated by external social constraints. This kind of violence is considered to be legitimated by the agreement to the social contract. This might be easier to understand if you imagine a medical scenario.

Say you have broken a bone and you are in pain. A doctor might say that the bone needs to be set; this will be painful, and kind of a forceful, “violent” action in which someone is interfering with your body in a painful way. So the doctor asks if you agree to let her set the bone. You agree, and so the doctor’s action is construed as being a legitimate interference with your body and your freedom.

If someone randomly just walked up to you and started pulling at the injured limb, this unagreed violence would not be considered legitimate. Likewise, when medical practitioners interfere with a patient’s body in a way that is non-consensual or not what the patient agreed to, then the violence is considered illegitimate, or morally bad.

We tend to think of violence as being another “normatively loaded” word, like authenticity. But where authenticity is usually loaded with a positive connotation–on the whole, people often value authenticity as a good thing–violence is loaded with a negative connotation. Yes, the doctor setting the bone is violent and invasive, but we don’t usually call this “violence” because it is considered to be a legitimate exercise of violence. Instead, we reserve the term “violence” mostly for describing forms of interference that we consider to be morally bad.

17.4.2. A Bit of History#

In much of mainstream Western thought, the individual’s right to freedom is taken as a supreme moral good, and so anything that is viewed as an illegitimate interference with that individual freedom is considered violence or violation. In the founding of the United States, one thing on people’s minds was the way that in a Britain riddled with factions and disagreement, people of one subgroup could not speak freely when another subgroup was in power. This case was unusual because instead of one group being consistently dominant, the Catholic and Protestant communities alternated between being dominant and being oppressed, based on who was king or queen. So the United States wanted to reinforce what they saw as the value of individual freedoms by writing it into the formal, explicit part of our social contract. Thus, we got the famous First Amendment to the Constitution, saying that individuals’ right to freely express themselves in speech, in their religion, in their gatherings, and so on could not legally be interfered with.

As a principle, the concept is pretty clear: let people do their thing. But we do still live in a society which does not permit total freedom to do whatever one wants, with no consequences. Some actions do too much damage, and would undermine the society of freedom, so those actions are written into the law (that is, proscribed) as a basis for reprisals. This happens a few ways:

Some are proscribed as crimes that lead to arrest, trial, and possibly incarceration.

Some are proscribed as concepts or categories of thing, which a person could use to take someone else to court. For example, copyright infringement doesn’t usually result in someone showing up to arrest and imprison in the States. But if someone believes their copyrights have been violated, they can sue the offending party for damages pay, etc. The concept of copyright is proscribed in law, so it forms the basis for such lawsuits.

Beyond what is proscribed by law, there are plenty of other actions and behaviors we don’t want people to be doing in our society, but they are not such as should be written into law. I don’t want my friends to lie to me, generally speaking, but this is not against the law. It would be weird if it was! Plain old lying isn’t proscribed, but perjury is (lying under oath in a court of law). The protections of freedom in the First Amendment were designed to help articulate a separation between what we might not like (e.g., someone having a different faith, or someone lying) and what is actually damaging enough to warrant formal legal mechanisms for reprisal (e.g. perjury). The Catholics and the Protestants don’t need to like each other, but they have the right to coexist in this society regardless of which group currently has a monarch on the throne.

17.4.3. So what is harassment?#

One useful way to think about harassment is that it is often a pattern of behavior that exploits the distinction between things that are legally proscribed and things that are hurtful, but not so harmful as to be explicitly prohibit by law given the protection of freedoms. Let’s use an example to clarify.

Suppose it’s been raining all day, and as I walk down the sidewalk, a car drives by, spraying me with water from the road. This does not make me happy. It makes me uncomfortable, since my clothes are wet, and it could hurt me if wet clothes means I get so cold I become ill. Or it could hurt me if I were on my way to an important interview, for which I will now show up looking sloppy. But the car has done nothing wrong, from a legal standpoint. There is no legal basis for reprisals, and indeed it would seem quite ridiculous if I tried to prosecute someone for having splashed me by driving near me. In a shared world, we sometimes wind up in each others’ splash zones.

Now, suppose it was more dramatic than that. Suppose the car had to really veer to spray me with the puddle, such that they could be described as driving recklessly, if anyone happened to be describing it. This is not the splash zone of regular living; it’s malice. But it’s still not illegal, nor the basis for legal action.

Finally, suppose it’s not just one car. There is a whole caravan of cars. I recognize the drivers as classmates whom I don’t get along with. They have planned a coordinated strike, each driving through the puddles so fast I can’t hardly catch a breath between splashes. My bag is soaked; my laptop and phone permanently damaged. Since damaging someone else’s private property is proscribed, I could try to prosecute the drivers. I have no idea if this hypothetical case would get anywhere in a real court, but if I could get a judge onside, they might issue a fine, to be paid by the drivers, to answer for my damages (that is, to pay for the replacement of my private property which was destroyed, specifically my laptop and phone).

At a guess, I would suspect that it would be very difficult to get anywhere with such a suit in court. Puddle-based harassment isn’t something that is recognized by law. This is what harassment does: it uses a pattern of minorly hurtful actions, so that the harasser can maintain plausible deniability about intent to harm, or at least, failing that, can avoid formal consequences.

When harassment concepts get proscribed, this situation shifts. Think about employment law in the States. Depending on what State you’re in and what sector, employment law does not permit racial harassment in the workplace. This means that if you can show a pattern of repeating behavior which is hurtful and based on racially coded comments, then you might have a viable case for a racial harassment suit. (Practically, this probably doesn’t mean suing. It means notifying HR that you have evidence of the pattern and request that they take disciplinary action. What the law does is say that if the harassing party subsequently sues for something like wrongful termination, the company has a legal basis for construing your evidence as showing a pattern of harassment.)

If there were a rise in, or a new recognition of, widespread and harmful puddle-based harassment, we might gather with activists and fight to get puddle-based harassment recognized by law, in order to reduce its occurrence. Not that this would be easy, but it would give us the legal basis for pressing charges when coordinated puddle-attacks occur. Getting the action proscribed by the law doesn’t stop people from taking that action. They are still free to puddle-splash at will. But there would be a possibility of consequences, should their pedestrian victims seek reprisal.

Harassment is behavior which uses a pattern of actions which are permissible by law, but still hurtful.

Variations:

Where a relevant harassment definition exists in law, there can be legal consequences.

Other institutions can also make their own harassment policies. The consequences would not arise at the legal level, but at the social level. Many universities have policies about sexual harassment which are much richer and more detailed than statutory law. If behavior is reported which is defined by the university policy as harassment, then they can issue consequences such as suspension of the student.

Implicit policies can be implemented as well. I don’t have a formal harassment policy that I require my houseguests to sign before entering my home; but it is my home, and if they start behaving in ways that I consider problematic, I do have the right to kick them out of my house.

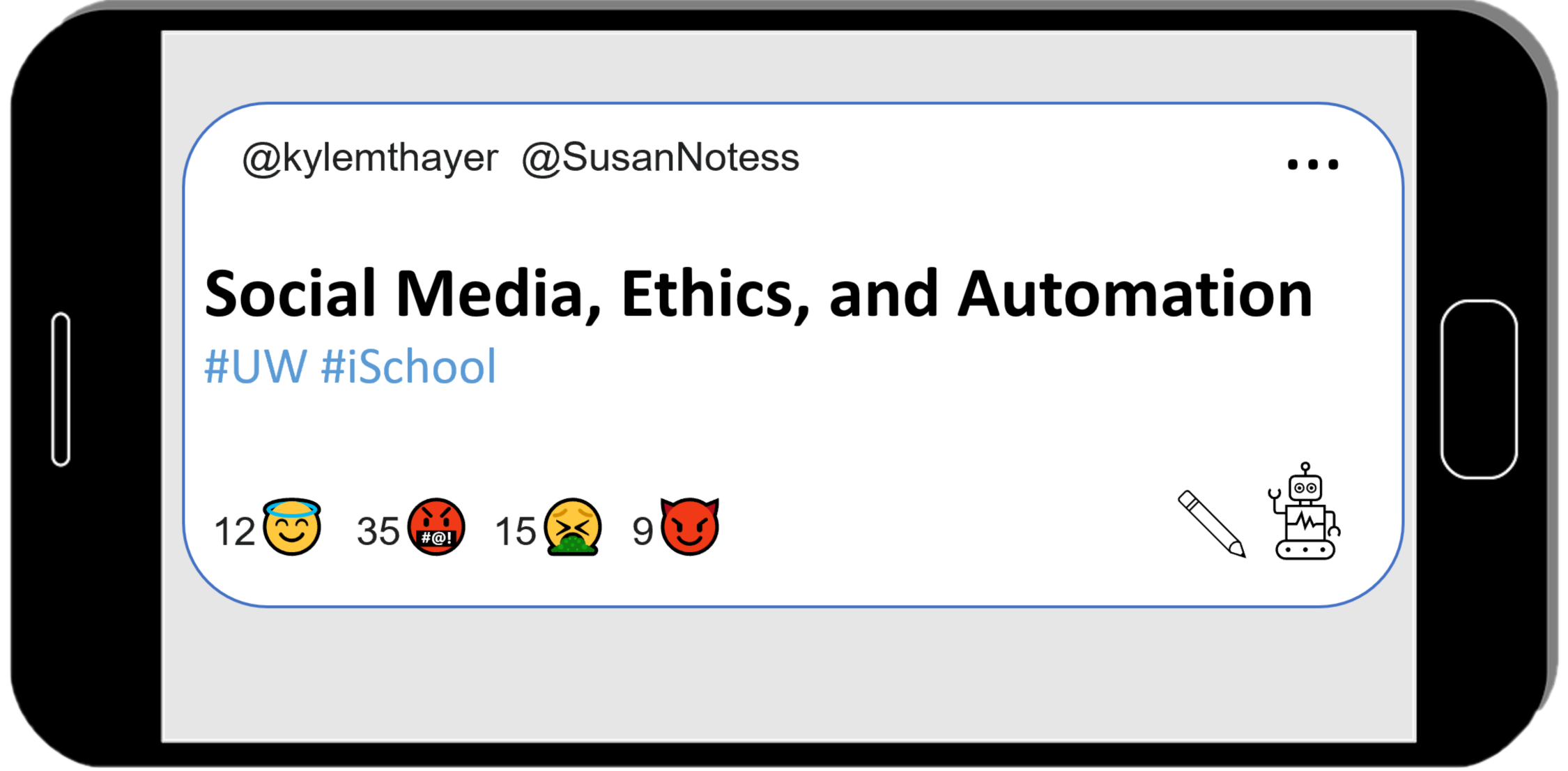

Harassment in social media contexts can be difficult to define, especially when the harassment pattern is created by a collective of seemingly unconnected people. Maybe each individual action can be read as unpleasant but technically okay. But taken together, all the instances of the pattern lead up to a level of harm done to the victim which can do real damage.

Because social media spaces are to some extent private spaces, the moderators of those spaces can ask someone to leave if they wish. A Facebook group may have a ‘policy’ listed in the group info, which spells out the conditions under which a person might be blocked from the group. As a Facebook user, I could decide that I don’t like the way someone is posting on my wall; I could block them, with or without warning, much as if I were asking a guest to leave my house.

In the next section, we will look in more detail about when harassment tactics get used; how they get justified, and what all this means in the context of social media.